Vive La Difference?

May 3, 2019

The State of Preschool 2018 Yearbook included a section on the state-funded preschool workforce, specifically focusing on salaries, benefits, and other policies in place to support preschool teachers. The picture the survey painted is grim. State-funded preschool teachers are rarely supported at the same level as their K-3 counterparts. And, preschool teachers in participating privately owned centers are even less likely to receive parity with their similarly qualified peers in public schools.

Yet as bleak as the picture is for the preschool teachers, perhaps it has been improving? To get a sense of change, we looked back at workforce policies three years ago, as reported in the State of Preschool 2015. Technically speaking, there has been progress, but it’s not exactly cause for celebration.

The salary gap between similarly qualified preschool teachers in public versus community-based settings has improved only minimally over the past three years. For states reporting average salary data, and adjusting for inflation, gaps in 2015 ranged from $3,128 to $25,076 while gaps in 2018 were $1,545 to $21,136. That is change in the right direction, but not much.

Looking at gaps in average salaries for state-funded preschool and K-3 teachers with a BA suggests somewhat more change: from $10,858 to $7,440 for preschool teachers in public schools and from $25,874 to $18,855 for preschool teachers in private settings. That is real progress but still leaves an average pay gap near $20,000 a year for highly qualified preschool teachers in private providers.

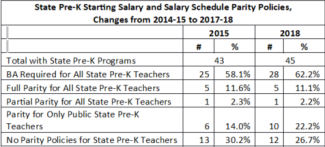

The reasons for this pattern of continuing pre-K teacher pay gaps are easily identified. The number of states requiring their program’s pre-K teachers to hold a BA increased, but the number requiring starting salary and salary schedule parity for all teachers has stalled at just five (see table below), and the number requiring parity for teachers in public schools only has grown. It’s promising to see that additional states are requiring preschool teachers to hold a BA but discouraging to see that adequate wage policies have not followed.

Turning to fringe benefits, the last three years have seen improvement. Eleven more states require K-3 equivalent fringe benefits for state-funded preschool teachers in public school settings (see table below). However, only two states added policies to require K-3 equivalent fringe benefits for preschool teachers in both regardless of location. Despite the progress over 50% of states still have no benefit parity policies at all for state-funded preschool teachers, regardless of where they teach.

Overall, the change story is very mixed. For those in public schools at least, there has been meaningful improvement in just the last 3 years. Yet most state pre-K programs use mixed delivery systems and progress for teachers in their private providers has been minimal. For them, its “plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose.” The fact is that we lay the same high expectations on our preschool teachers regardless of where they teach while compensating them very differently from their peers and each other. This kind of disparate treatment would be unthinkable in other sectors of the economy, government, or public education. It should be unthinkable in preschool programs, too.

The Authors

Karin Garver is an Early Childhood Education Policy Specialist at NIEER. Her research interests are in national and state early education policy trends, inclusive opportunities for preschool children with disabilities, data systems, systems integration, and public program finance.

About NIEER

The National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) at the Graduate School of Education, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, conducts and disseminates independent research and analysis to inform early childhood education policy.