Playing Fair

Teacher Compensation Parity Policies and State Funded Pre-K Programs

April 25, 2017

Compensation parity is a critical goal in the pursuit of a well-qualified, stable prekindergarten workforce, especially given the low wages and high demands pre-K teachers face.

A recent National Academies of Science report, Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation, found that facilitating early learning and development requires knowledge and skills as complex as those needed to teach older children. And, as more states have launched public pre-K program, many pre-K teachers are required to hold a bachelor’s degree. Yet, on average, a public pre-K teacher with a bachelor’s degree can expect to earn around $12,000 less than a public kindergarten teacher with similar credentials, according to NIEER’s 2015 State of Preschool Yearbook. A pre-K teacher in a community-based or other private program faces a wage gap averaging $27,000. Such gaps, combined with increased stress and burnout, can contribute to high turnover rates among prekindergarten teachers, which can lower classroom quality and hamper early learning opportunities for children.

To document the extent of the compensation parity issue among public pre-K programs and identify programs providing parity for pre-K teachers, NIEER has partnered with the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment (CSCCE). In two policy briefs, In Pursuit of Pre-K Parity: A Proposed Framework for Understanding and Advancing Policy and Practice, and Teacher Compensation Parity Policies and State Funded Pre-K Programs, we look at the landscape of compensation parity policy—policies seeking to improve financial rewards for teaching preschool relative to teaching older children.

Our framework clarifies components of compensation parity policy and classifies state-funded pre-K programs in terms of compensation for lead and assistant teachers, based on workforce data collected by NIEER for the 2015 State of Preschool Yearbook. We define “parity” as providing the same compensation to pre-K teachers as K-3 for equivalent levels of education and experience, adjusted to reflect differences in hours worked in private settings.

Our review showed 10 states have parity policies for lead pre-K teachers in salary, benefits, and payment for professional development and planning time. Only four states have compensation parity policies for pre-K assistant teachers. Benefits parity policy is the most prevalent, with 15 states having benefits parity policies for both pre-K lead and assistant teachers. However, 24 states—more than half of the 44 states running state-funded prekindergarten—have no compensation parity policies for their teachers. See full report w/link.

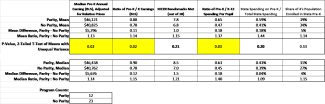

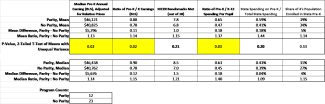

NIEER data also looked at evidence of the relationship between salary parity policy for lead teachers, actual salaries, and various measures of investment in pre-K. Findings suggest salary parity policy is related to state commitment to pre-K investment. In programs with salary parity policies for pre-K teachers:

- Lead teacher pre-K salaries are higher

- The ratio of public pre-K to K-12 spending per pupil is higher

- More NIEER State of Preschool Yearbook benchmarks were met (although not at a statistically significant level)

- Parity does not come at the expense of enrollment; NIEER found no statistically significant difference in the share of the 4-year-old population enrolled in states with salary parity relative to those without parity.

We hope these briefs advance discussion about what compensation parity means and requires. Our preliminary investigation illustrates a variety of approaches states have taken to compensation parity. Four states—New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, and Tennessee—have full compensation parity policy for lead and assistant teachers across all three components of compensation. Yet even for these states, some policies are only extended for teachers physically working in public settings—an important distinction given many state pre-K programs run classrooms in nonpublic settings.

There is evidence that state programs with salary parity policy show signs of greater overall resource investment in pre-K. But with more than half of the states with state-funded pre-K report providing no compensation parity at all, clearly, more needs to be done to make pre-K teacher compensation commensurate with the skills needed to perform this highly demanding and important work.

Table 1: How Pre-K Programs with Salary Parity Policy Compare to Programs without Parity Policy—Various Metrics of Salary and Investment

Richard Kasmin is a research project coordinator at the National Institute for Early Childhood Education (NIEER). His primary research responsibility is analysis of early childhood education finance. In that role, Richard is focused on understanding the methods by which states raise and distribute funding for early childhood education and the inherent implications for program development. He is also heavily involved in the production of NIEER’s State of Preschool Yearbook and collaborates on projects with the Center on Enhanced Early Learning Outcomes (CEELO).

About NIEER

The National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) at the Graduate School of Education, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, conducts and disseminates independent research and analysis to inform early childhood education policy.