Local Control in Early Education

October 16, 2013

Local control, or at least the perception of its presence, is a closely guarded tenet in state and local politics. It provides citizens with a sense of purpose, identity, autonomy, and power, allowing local constituents to influence the policies and programs affecting them right in their front yards. We see this in matters such as states’ and communities’ taxes or property rights. Education is perhaps the single most engaging issue when it comes to local control, and its reach into early education policy and practice is becoming increasingly evident, as more children enroll in state-funded pre-K programs.

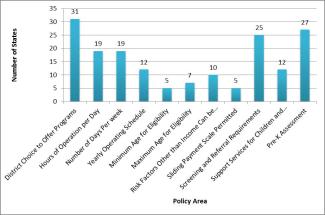

Results of the NIEER 2012 State Preschool Yearbook indicate that provisions for local control are infused in legislation and regulation for pre-K policy and practice in all 40 states and the District of Columbia with state-funded pre-K programs (Figure 1). Looking across eleven measures, all 54 programs across these states and DC report at least one instance of districts being authorized to exercise local control in decision making.

The Compass Points Northeast

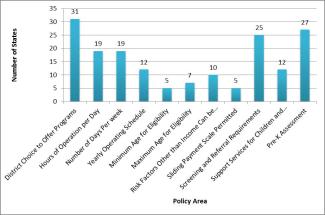

States vary in the latitude they permit local control of state pre-K policies and practices (Figure 2). Northern New England states demonstrate the greatest evidence of local control. Massachusetts reported the most options for local control policy among all programs, appearing in 8 of 11 areas, with Maine and Vermont permitting local decisions in 7 areas. At the other end of the continuum, Arizona, New York, Rhode Island, and one South Carolina program reported local decision-making in only a single policy area, with 7 additional states allowing 2 policy areas to be determined locally. States with multiple pre-K programs often see variations across their programs. Seven states with multiple pre-K programs (Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Wisconsin) permitted differing levels of local control across programs while only Vermont and the District of Columbia shared aligned options for their programs.

Looking closely at 11 survey questions that included “locally determined” as a response option, several categories emerged in which local control shaped program design: Access and Eligibility, Operating Schedules, Supplemental Services, and Child Assessment.

Access and Eligibility

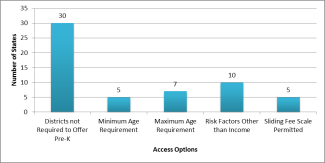

State requirements for districts to offer pre-K programs was the most frequent policy option demonstrating local control: 41 programs in 30 states and DC indicated some level of local choice. In some situations responses were based on a district’s decision to offer the program, in others it was influenced by a state’s ability to competitively fund a limited number of programs or slots.

Local programs in several states were afforded discretion in defining the age at which children may enroll in state-funded pre-K. Massachusetts, Nebraska, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Vermont allowed local districts to establish a minimum age for participation (sometimes within defined parameters) and seven states (Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Vermont, and Wisconsin) permitted local determination of a maximum age limit, including provisions for districts to issue waivers.

Eleven programs in 10 states allowed local communities to establish specific risk factors other than income to determine eligibility.

Operating Schedules

Three survey questions addressed operating schedules of state-funded pre-K programs. Policies in 18 of 40 states and the District of Columbia allowed individual programs to determine the number of hours per day each would operate. Eighteen states and the District of Columbia exercised local control when determining how many days per week programs would operate, and the number of weeks per year was locally determined in 12 states.

Supplemental Services

Two questions in the survey where local control were frequently reported addressed services supplementing the educational program. Screening and referral requirements examined provisions for vision, hearing, health, and behavioral assessment with follow-up. Thirty-four programs in 24 states and DC allowed each site to determine which, if any, screening and referral services would be provided.

DC and 11 states offered local control options for support services for children and families, including nutrition services, parent education, child and family health services, home visits, transition to school activities, and parent conferences.

Child Assessment

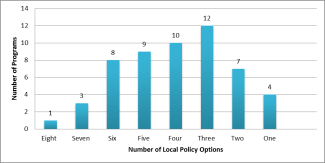

States provided information about policies regarding local choice for child assessment instruments used in their state pre-K programs (Figure 3). Thirteen states required that programs use defined instruments for pre-K assessment, while 12 others allowed local programs to decide which instrument or instruments would be used. Eight states reported no policy requirements for use of a pre-K assessment, while 10 allowed limited choice from a menu of approved instruments, all aligned to the state’s early learning standards.

Flexibility permitted programs to choose assessments aligned with state early learning standards and match the goals and priorities of individual program. Sixteen different pre-K child assessment instruments were identified by states and Washington DC, with performance-based Teaching Strategies GOLD and the Work Sampling System appearing most frequently.

An Array of Choices, But at What Cost?

As data clearly indicate, local control is alive and well in policies across state pre-K programs. In some situations, programs are able to determine “what” they do, in others it is a matter of “how” to do it. Either way, decisions about program operations are not set in stone.

Certainly, there are advantages to local determination of program policies and practices. It affords greater grassroots involvement recognizing that people live in communities, not in the aisles of the state house, where most are aware of what is wanted and needed in relation to community values. Stakeholders invest their time, energy, and resources when they feel their involvement contributes to a genuine difference they can see. Local control fuels a sense of empowerment among educators, administrators, and policymakers. Further, local control fosters innovation. Conventional wisdom recognizes that not all communities are created equal, so creative solutions must take advantage of available resources and talents. As the altered adage states, “One size fits one.”

Ah, did someone just mention “Equity” when looking at these data? Clearly, there is a downside to local control as well. Zip codes across and within states define opportunities for children in terms of access and services. Local control may be associated with, or the cause of, inequalities of opportunity, disparities in resources, and gaps in achievement that persist despite political posturing and wrangling. Nine states continue to lack state-funded pre-K (although efforts are underway in several states) and even in states with pre-K many children are not being served at all and those that are may be getting quite different services.

The issue of state or local control may be moot, however, if there is insufficient oversight of program quality. The best policies make little difference for children unless they are enacted; and monitoring is critical to ensure implementation with fidelity to produce intended results for children and measures of accountability for state and local leaders. Too often, local control results in a myopic view of the state of affairs or leaves local leaders sorting through a bushel of apples and oranges unable to make sense of what went awry and for what reasons.

– Jim Squires, Senior Research Fellow

– Michelle Horowitz, Research Assistant

The Authors

About NIEER

The National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) at the Graduate School of Education, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, conducts and disseminates independent research and analysis to inform early childhood education policy.