Behind the Numbers

How State Preschool Has Changed Since 2002

April 18, 2019

NIEER released its 16th State of Preschool report this week, once again providing information on enrollment, spending, and policies, especially those related to quality. This is a complex report and so we have written this blog to help readers get behind the numbers to what it all means.

The State of Preschool is both a national report and a report on 62 separate state-funded preschool programs across 44 states, the District of Columbia, and Guam. NIEER also reports on six states that do not fund pre-K programs. Almost no policy is the same across all the pre-K states.

Our annual report also highlights change, describing not only where we are now, but also where we have been–and how we got here.

In many ways, state-funded preschool has changed since 2002; yet in other ways, it has remained the same. In 2018, 44 states provided funding for preschool; this is up from a low of 38 states. (Indiana and Utah might be added under a looser definition of state preschool education).

Follow the money is always good advice when investigating politics and policy. State spending has increased substantially from $2.4 billion in 2002 to $8.1 billion in 2018. This large change is potentially misleading if we don’t adjust for inflation. Adjusted to 2018 dollars, states spent $3.9 billion in 2002 so we are looking at real purchasing power for pre-K just about doubling–rather than more than tripling.

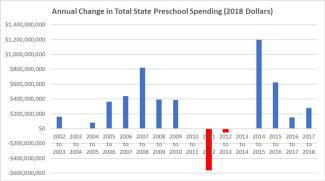

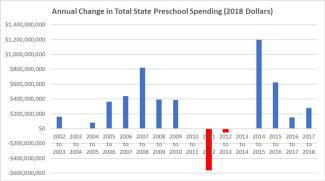

In our experience, advocates and even some policy makers seem to suffer from what economists call “money illusion,” failing to take account of inflation and celebrating as gains what are really losses. As the figure below shows, when we adjust for inflation, total funding decreased four years in a row from 2010 to 2014, in the wake of the Great Recession (though in all but one of those years the decrease was slight). Although there was a sharp one-year partial recovery, recent spending growth has been weak.

How programs changed: access, duration, and quality. Enrollment increased just slightly more than in proportion to funding, about 2.25 times, from fewer than 700,000 children in 2002 to nearly 1.6 million in 2018. However, that slightly higher level of enrollment growth compared to total spending was enough to decrease spending per child by about $400 (adjusted for inflation) over this same period.

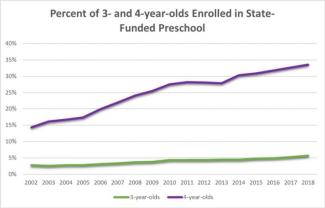

Changes varied greatly by age of child. Nationally, the US went from enrolling 14% of all 4-year-olds to 33%, but the country only progressed from 3% of 3-year-olds to 5.5% of 3-year-olds. As would be expected from the spending pattern, growth in enrollment took a hit after the Great Recession. Though enrollment has increased each year since, the rate of change has never fully recovered to pre-recession speed.

Not all states can report enrollment by program operating schedule, but among those that can, there has been considerable change in many states from part- to school-day programs over the past decade. Thirty-percent of these states have always served all children in at least school-day programs; and 60% increased the percent of children enrolled in preschool who were in school-day pre-K programs. Nevada, Michigan, and New York led the progress (while Alabama, Arkansas, DC, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Tennessee have served all children in school-day programs for the last ten years).

Beyond increasing the number of children served and program duration, states also increased investment in quality to ensure children truly benefit. Many states are meeting more of NIEER’s 10 minimum quality standards benchmarks since 2002; although many still have a long way to go–including some states serving the largest numbers of children living in poverty. In the past three years, NIEER revised the benchmarks to make some more rigorous, as all or nearly all states met them, and changed others to reflect research linking supports for process (implementation) and program quality with child outcomes.

The states that changed most include some of the largest with the greatest numbers of disadvantaged children. Only Oklahoma and Georgia served half of their 4-year-olds in 2002; today (2018) there are 10 states that do so, including Florida, Texas and New York. The biggest state, California, has yet to join them, but rose from 14% to 37% from 2002 to 2018, so that it is now ahead of the national average.

Alabama, Rhode Island, and Vermont might be considered “the little engines that could,” with Alabama moving from serving 1% in 2002 to 28% in 2018 (32% in 2019) at age 4 and from meeting 7 benchmarks to meeting all 10. Rhode Island moved from no program to enrolling 10% of 4-year-olds statewide and also meeting all 10 benchmarks. Vermont’s enrollment increased from 5% at age 3 and 9% at age 4 in 2002 to 62% and 76%, respectively, in 2018.

Nevertheless, we need to accelerate change for the better. At the current rate of change, it will take 75 years to reach kindergarten levels of enrollment for 4-year-olds in preschool and Head Start; it will take 175 years for 3-year-olds. These time estimates do not account for program quality–it would likely take even longer to ensure all of these children had access to high-quality, school-day preschool.

As we look back over the years, NIEER applauds states on the progress they have made, but clearly much more is needed, and with children, there is no time to waste.

Dr. Friedman-Krauss is an Assistant Research Professor at NIEER and co-author of The State of Preschool 2018, and prior yearbook reports. Her research focuses on (1) unpacking impacts of early education interventions, (2) early education quality, and (3) the cognitive and social-emotional development of low-income children.

Dr. Barnett is Founding Director of NIEER and a Board of Governors Professor at Rutgers University. His research includes studies of the economics of early care and education including costs and benefits, the long-term effects of preschool programs on children’s learning and development, and the distribution of educational opportunities.

The Authors

Allison Friedman-Krauss is an Associate Research Professor at NIEER where she is also the Associate Director for Policy Research and Director of the Infant and Toddler Policy Research Center.

W. Steven (Steve) Barnett is a Board of Governors Professor and the founder and Senior Co-Director of the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) at Rutgers University. Dr. Barnett’s work primarily focuses on public policies regarding early childhood education, child care, and child development.

About NIEER

The National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) at the Graduate School of Education, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, conducts and disseminates independent research and analysis to inform early childhood education policy.