Emergency Preparation in Early Education Programs

October 29, 2013

Many families make emergency preparedness a priority in the home, explaining to small children what to do in case of a fire, devising “family reunification plans,” and stocking up on supplies in case of an emergency. However, a recent report indicates that schools and child care centers may not be giving safety the same focus. A year out from Hurricane Sandy, we’re providing resources on preparing for and recovering from emergencies, with a special focus on children.

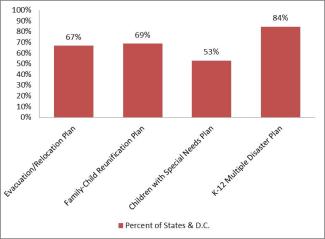

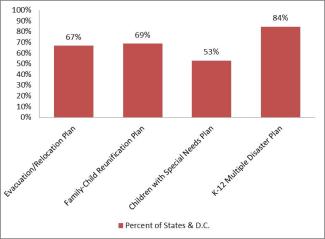

Save the Children released its annual report examining state-by-state policies on emergency preparedness policies. Highlighting incidents as diverse as hurricanes, tornadoes, and school shootings, Save the Children graded the nation’s overall response on planning protection for children as “unsatisfactory.” Save the Children graded states on whether they required school and child care centers to meet the following four recommendations from the National Commission on Children and Disasters:

- Evacuation/Relocation Plan: All categories of child care providers have a written plan covering multiple situations for evacuating children and safely relocating them to an alternate site.

- Family-Child Reunification Plan: All categories of child care providers have a written plan for notifying parents in the event of an emergency, and reuniting children with their families.

- Children with Special Needs Plan: All categories of child care providers have a written plan specifying how the needs of children with disabilities and those with access and functional needs would be addressed in the case of an emergency.

- K-12 Multiple Disaster Plan: All public schools, including charter schools, to have a written plan that covers a number of emergency scenarios, including those resulting in evacuation, lock-down, and shelter-in-place. Fire/tornado drills alone are not adequate to address these needs.

States vary widely in meeting each standard (see Figure 1). Particularly troubling is the fact that just over half (53 percent) of states require detailed plans from child care centers explaining how they would tend to the special needs of children with disabilities during an emergency. For children with special needs–perhaps a child with autism who is overwhelmed by the sound of a fire alarm or a child with limited mobility because he is in a wheelchair–special attention is particularly important.

Save the Children also provides an interactive map to explore which states require each policy. While the grades in the report focus specifically on the need to improve state policies, Save the Children also offers resources to support both child care providers and families in developing emergencies plans. The basic guidance is the same for both:

- Make a plan

- Have a communications strategy

- Practice emergency drills, and teach children skills like calling 911

- Create a disaster kit, including important documents, first aid supplies, activities to entertain children, and food

Natural disasters and violence are dangerous for anyone, but young children are particularly susceptible to negative consequences, as “toxic stress” can have both short- and long-term impacts when it occurs during a crucial period of brain development. The Center for the Developing Child at Harvard University provides resources documenting the effects of such stress, along with recommendations for prevention and remediation, including a “Tackling Toxic Stress” series. Center-based learning experiences can help children cope with such stress, as highlighted in a recent NIEER brief, particularly when coupled with supports like parenting programs and home-visiting, to reduce toxic stress in the home.

There must also be a focus on how to help kids cope with tragedy they’ve already experienced. As we saw repeatedly in 2012 – with the tornadoes in Moore, Oklahoma; the Sandy Hook Elementary School shootings; and in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, which Save the Children reports impacted over 250 child care centers about a year ago– schools can be ground zero for both tragedy and recovery. Here’s how parents and teachers can help mitigate the emotional turmoil kids experience.

- The Federal Emergency Management Agency provides tips on coping with disaster, organized by children’s age range.

- The Federal Office of Head Start has numerous resources on helping children in Head Start programs through emergencies, including resources on social-emotional support for both children and adults and an Emergency Preparedness Manual for providers.

- Parents and teachers may be unsure how to talk to children about what they have experienced without adding stress. PBS provides general information on how to talk to children about news in an age-appropriate way.

- The National Association of School Psychologists provides tips for talking to children about violence that can also guide conversations after natural disasters.

- Sesame Street offers a number of interactive resources for parents and children addressing emergencies, mostly focused on natural disasters.

It is particularly unpleasant to think about disasters affecting children in schools and child care centers–places that are meant to be safe spaces for growth and exploration–but it is the responsibility of all adults who care for children to face this task. The Fred Rogers Company provides guidance on how to help children navigate scary events with Mr. Rogers’ classic advice:

“When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, “Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.” To this day, especially in times of “disaster,” I remember my mother’s words and I am always comforted by realizing that there are still so many helpers–so many caring people in this world.“

Policymakers, parents, and program directors can be those helpers.

-Megan Carolan, Policy Research Coordinator

About NIEER

The National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) at the Graduate School of Education, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, conducts and disseminates independent research and analysis to inform early childhood education policy.