Remote schooling failed our preschoolers.

We have to do better.

July 30, 2020

With four children under the age of 9, I am among our nation’s millions of parents dramatically affected by school closures due to the pandemic. Our old normal was replaced by a new normal of uncertainty and chaos. What comes next? How do we support our children while taking on new roles at home as teachers, specialists, and therapists? And how do we manage all this while trying (if we’re fortunate) to keep our jobs?

As an education researcher with nearly 20 years of experience, I felt fortunate to understand what my preschooler needed and to have access to many resources. But as a mother, the packages containing ideas and activities snail mailed by my school district made little sense. I could not shake the feeling my 4-year-old’s public preschool program was failing him and his peers. After establishing some sense of normalcy around my kids’ routines and their learning, I started to build a learning (and bilingual) toolbox to work with my preschooler at home. Equity is a central perspective throughout my research, so I couldn’t help but wonder about other families left to work through this national experiment on their own.

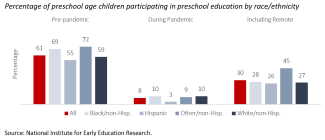

My colleagues and I conducted a nationally representative survey study of nearly 1000 parents of children ages 3 to 5 and not yet in kindergarten to assess the impact of the pandemic on young children and their families. As we all know about 90% of preschool classrooms closed in March. Less well known is that most of us received little support to continue educating our young children at home. Before the pandemic, 61% of preschool age children attended a preschool program, but only 8% of children continued in-person and no more than 30% continued to receive preschool education even counting families that had remote supports through the rest of the school year. This huge reduction in preschool services affected all groups of parents regardless of child and family background characteristics including race/ethnicity, parental education, and income.

Source: (Barnett, Jung, Nores, 2020)

As I worked with my pre-K child to create different variations of sorting exercises, expand his access to online reading resources, and reproduce the sounds of letters he was having speech issues with, I was sure this new reality would exacerbate inequalities by the time children reach Kindergarten.

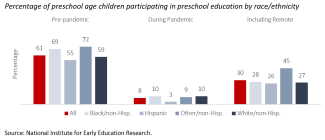

It turns out only 72% of parents whose preschool programs closed ever had any contact with their child’s teacher, 60% of these programs seemed to have been using worksheets as part of their remote instruction, and more than half of children received digital and/or paper-based supports. About a third received pre-recorded videos to support their learning. On top of all this, only 37% of children with an Individualized Education Programs (IEP) were receiving full support.

Source: (Barnett, Jung, Nores, 2020)

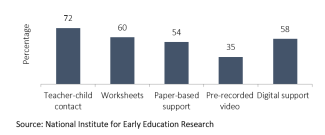

To capture the degree and frequency to which preschool children were being effectively supported, the NIEER PLA survey also asked parents how often each week their programs provided ten specific types of activities. My heart sank reading the responses. About two thirds of the programs did not support reading in any form at least once every week, nor did they support online activities with the teacher or classmates, or any math or science activities, arts and music, or physical activities.

Source: (Barnett, Jung, Nores, 2020)

Early education research has provided effective guidance on how to reduce inequities by the time a child enters Kindergarten, and we have invested millions in preschool programs to reduce inequities. Yet, this pandemic has revealed how woefully unprepared programs were to support and provide children an effective remote preschool experience. The consequences will likely be substantial. The vast majority of preschool-age children seem to have lost two to four months of learning experiences; with most districts across the country unable to implement a good substitute to in-person learning. In a 2016 study we reported the size of the skills gap at Kindergarten entry was as much as 13 months. Relying solely on family resources, which are likely under great strain due to the pandemic and the job losses is caused, will likely have widened this gap. The results from our survey strongly suggest a generation of preschool children will face long-term negative consequences in their development because preschool systems failed to adequately respond to the pandemic.

Programs are now deciding if and how to reopen and considering remote-based preschool service options. They must first review and learn from their unpreparedness for remote support. All future virtual preschool programs need to establish a strong foundation that connects parents with intentionally curated resources, and focus deeply on unconstrained skills. They must also develop strategies for offering strong preschool experiences that provide the depth our preschoolers need to succeed.

About NIEER

The National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) at the Graduate School of Education, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, conducts and disseminates independent research and analysis to inform early childhood education policy.